NEWS: Whites, males comprise big majority of state university governing boards

NEWS: Whites, males comprise big majority of state university governing boards

NEWS BRIEFS: New CHE head begins post, opioid epicenter, hot cars, more

COMMENTARY, Brack: Run, Mark Sanford, Run

SPOTLIGHT: The S.C. Education Association

FEEDBACK: USC’s board is the problem, not Caslen

MYSTERY PHOTO: Speed limit: 25 mph

S.C. ENCYCLOPEDIA: University of South Carolina

NEWSWhites, males comprise big majority of state university governing boards

By Lindsay Street, Statehouse correspondent | You almost need a fine-toothed comb to find anyone other than a white man on public university governing boards in South Carolina.

This conclusion comes from a new Statehouse Report review of South Carolina’s public universities. It found governing board members are 75.8 percent male and 84.5 percent white — and zero members were of Latino, Asian or Native American ethnicity.

Having boards that are more than white and male are important, Senate Education chair Greg Hembree, R-Horry, told Statehouse Report.

“You want to get diversity and experience and perspective,” he said. “First and foremost, you want the best people to do the job. However, on the second part of that, women have a different perspective then men many times, and people of different races have different perspectives.”

Of South Carolina’s 161 public university board members, including ex-officio members, 39 were female and 25 were black. The review was pulled from a public data request made to the institutions as well as a review of university websites. Half of state universities complied with the request, with the other half leaving it up to the publication to infer race and gender for trustees.

The University of South Carolina, which has a controversial board meeting today purportedly to pick a new president, has a governing board that is 88.9 percent male and 94.1 percent white. It did not directly respond to the request for information, citing today’s vote.

USC has the lowest percentage of women serving (tied with S.C. State University at 11.1 percent) and the second lowest percentage of African Americans (5.9 percent) serving on its board.

In an opinion piece published Thursday in Inside Higher Education, USC alumnus and My Carolina Veterans Alumni Council founder James L. Anderson bemoaned the lack of diversity on his alma mater’s governing board and among S.C. higher education institutions’ trustees:

“The makeup of public boards for universities and colleges is heavily skewed toward white, male baby boomers.”

Winthrop leads in board diversity

The state’s only public historically black college, S.C. State University, had the highest rate of black trustees at 67 percent, but also the lowest rate of women serving on the board (11.1 percent), according to our analysis

The state’s only public historically black college, S.C. State University, had the highest rate of black trustees at 67 percent, but also the lowest rate of women serving on the board (11.1 percent), according to our analysis

On the other hand, College of Charleston had one of the highest rates of women trustees (40 percent; only Winthrop and Lander universities were higher at 46.7 percent and 41.2 percent respectively), but had the lowest rate of black trustees at 5 percent.

More findings:

- Winthrop University had the second highest percentage of black trustees at 26.7 percent.

- Coastal Carolina University had the third lowest rate of black members serving (6.25 percent) and also the second lowest rate of women serving (12.5 percent).

- At the Medical University of South Carolina, women made up 12.5 percent of the board, and African Americans made up 12.5 percent of the board. At The Citadel, where its members must be alumni and it began accepting women since 1996, two of its 14-member board are women, accounting for 14.3 percent of members.

What’s being done

Governing boards in South Carolina public higher education vary in size from 12 to 20. While most trustees are elected by the General Assembly, the governor and alumni also make appointments. Some members are tied to congressional districts or, in the case of University of South Carolina, are tied to the state’s 16 judicial circuits.

Senate President Harvey Peeler, R-Cherokee, is chairman of the College and University Trustee Screening Commission, which reviews legislative-appointed candidates to the board. He did not respond to a Thursday request to comment.

The overwhelming majority of members of the General Assembly also are white and male.

Hembree is familiar with the university board election process, but does not oversee or take part in the screenings before the chambers vote on candidates. He said the commission only screens for qualifications. He said boards could encourage diversity through a governance committee, which would encourage qualified and diverse candidates to apply for seats.

“They would be in a position to say we have three lawyers on this board right now for goodness sake don’t send us another lawyer but we need an architect … whatever it might be,” Hembree said. “It’s not radical. It’s kind of smart and it’s very common in the private sector.”

Hembree said he was unaware of a governance committee for any public college in the state. The state Commission on Higher Education was also unable to provide that information.

He said he may explore a statute that would help provide “overarching guidance or direction” for board member selection.

Anderson said governing boards should also impose term limits to help become more diverse and reflective of its student body.

“A truly cross-generational and more diverse board is necessary to meet the opportunities and complex challenges of tomorrow,” Anderson wrote. “Term limits could be a first step toward reaching that goal.”

Another USC alumni, John Warner, penned an opinion piece in the same publication, partially in response to Anderson. He called for half of the board to be selected by students and faculty rather than lawmakers — a board composition that is not evident at any public university in the state.

Others have called for boards like USC’s to have fewer members.

How we obtained the data

On Monday, Statehouse Report requested the information of the state’s 10 publicly-funded higher education institutions: The Citadel, Clemson University, Coastal Carolina University, College of Charleston, Francis Marion University, Lander University, Medical University of South Carolina, S.C. State University, University of South Carolina, and Winthrop University.

Five responded with the demographic information requested by deadline.

Data from the other five universities was obtained by reviewing photographs and titles available on the schools’ websites. Because these five universities would not corroborate the findings, Statehouse Report recognizes it is possible that this information is incorrect as it is difficult to accurately discern race or gender from just a picture. However in the interest of providing a fuller picture for the story, the publication chose to make inferences. If readers find any of the data incorrect, please alert the publication.

Of the five universities that did not provide information on the public officials, only S.C. State University and Clemson University did not respond at all.

University of South Carolina spokesman Jeff Stensland responded Thursday, three days after the request:

“As you may or may not be aware, we are preparing for a board meeting tomorrow, so will not be able to provide you with all the information you requested by your deadline.”

Lander University spokeswoman Megan Varner also responded Thursday:

“We’re unable to provide this demographic information at this time, as we do not collect it from our trustees.”

Coastal Carolina University Chief of Staff Travis E. Overton said the publication needed to submit a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to obtain demographic information of its board. Such a public records request can take up to 14 business days, and was not required by any other public university in the state.

“I would need to defer to the FOIA Office to answer that question,” he wrote in an email. He did not respond to further requests for comment.

- Have a comment? Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com

NEWS BRIEFS

New CHE head begins post, opioid epicenter, hot cars, more

By Lindsay Street, Statehouse correspondent | Rusty Monhollon stepped into the Commission on Higher Education’s president and executive director office on Monday.

Monhollon was hired May 31 by the commission’s board. He replaces interim executive director Mike LeFever, who served after a tough 2018 for the commission where interim executive director Jeff Schilz and board chair Tim Hofferth resigned after Hofferth awarded Schilz a $91,500 raise.

In a previous position, Monhollon served as assistant commissioner for academic affairs at the Missouri Department of Higher Education.

The Commission on Higher Education provides statewide policy direction, management, and oversight of the state’s higher education enterprise.

Monhollon was reached for comment earlier this week on another story (see the Big Story), but asked for time to review the issue. After an email to Statehouse Report, he did not respond to the several follow-up requests for comment on his new position.

In other news:

![]() Opioid epicenter in Charleston County. A map by the Washington Post this week of Drug Enforcement Administration data showed Charleston County had an average of 248.3 pills per person dispensed per year of opioids from 2006 to 2012. It was the highest number of pills per person in the country. Statehouse Report reached out to Charleston County spokesman Shawn Smetana to see if the county was reconsidering joining or filling a prescription drug lawsuit. Smetana said the county’s position has not changed since the publication’s June 28 story.

Opioid epicenter in Charleston County. A map by the Washington Post this week of Drug Enforcement Administration data showed Charleston County had an average of 248.3 pills per person dispensed per year of opioids from 2006 to 2012. It was the highest number of pills per person in the country. Statehouse Report reached out to Charleston County spokesman Shawn Smetana to see if the county was reconsidering joining or filling a prescription drug lawsuit. Smetana said the county’s position has not changed since the publication’s June 28 story.

DeVos joins McMaster in touting private education. U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos visited the Midlands and Upstate South Carolina this week. She praised workforce development initiatives at pharmaceutical company Nephron, and spoke about the proposed federal program that offers scholarships to private schools at a private school in Taylors. Gov. Henry McMaster and state Superintendent of Education Molly Spearman joined her in Taylors. There, McMaster said education possibilities would be opened with the federal program. Read more.

State leads nation in hot-car deaths for children. Six children died in 2018 in S.C. after being trapped inside hot vehicles. Five of those children were left behind by caregivers and the sixth went into an unlocked, parked vehicle and succumbed to the heat. Experts say forgetting a child in the back seat is not a matter of loving your child, but a matter of multi-tasking and distractedness. The spike in hot-car deaths was also linked to the decrease in air-bag deaths for children, since children were moved to the back seat and more easily forgotten. Read more.

Santee Cooper to pay $15M for sale study. The Santee Cooper Board of Directors unanimously approved this week a payment of $15 million to help pay for a study to determine its sale. Read more.

2020 candidate calendar

Throughout the campaign season, we are working to keep South Carolina informed of candidate events in the state. Have an event you want us to know about? Email us at 2020news@statehousereport.com.

Biden. Former Vice President Joe Biden’s wife, Jill Biden, will hold a meet and greet 5:30 p.m. July 19 in Summerville.

Castro. Former Housing and Urban Development Secretary Julian Castro will hold town halls July 20 in Greenville and July 21 in Columbia.

Second debate scheduled for July 30, 31. Democrats vying for the party’s nomination in 2020 will convene for a two-part debate by CNN July 30 and 31 in Detroit. More info here.

Looking ahead

Click below for other items coming up in the Statehouse:

Find any bill

- House bills

- Senate bills

- Have a comment? Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com

BRACK: Run, Mark Sanford, Run

By Andy Brack, editor and publisher | This sentence would have been unimaginable in this space 15 years ago: Mark Sanford should run for president.

The often thin-skinned Sanford, out of the limelight for months since a surprise 2018 primary loss to a backer of President Trump, has been tinkering with the idea of taking on the divisive, narcissistic president.

The often thin-skinned Sanford, out of the limelight for months since a surprise 2018 primary loss to a backer of President Trump, has been tinkering with the idea of taking on the divisive, narcissistic president.

But Sanford shouldn’t employ a frontal political assault. Trump has screwed up the Republican Party that once stood for fiscal conservatism. Rather, Sanford should honor his libertarian penchant by running as an independent.

Why? Because Sanford is talking about something that matters and is being left out of the public debate: The nation’s oppressive and growing $22 trillion debt. As a comparison, President Bill Clinton inherited a national debt of about $4.5 trillion and left with a balanced budget and a debt of a trillion more. And back then, the late budget hawk, U.S. Sen. Fritz Hollings of South Carolina, was hollering his head off about profligate spending. Now it’s five times more of a burden.

In orchestrated media forays including “The View,” the former governor, who once ranked the most fiscally conservative member of the U.S. House, has been rightfully trying to steer the national conversation to the long-term burden of debt on the American economy and way of life. The borrow-and-spend culture that has infected the Republicans and Democrats in Washington is haunting our future. If we don’t start doing something about it, America will go the way of Great Britain.

Sanford, of course, is not the perfect messenger. As governor, he had a “my way or the highway” style that irritated the legislature and doomed many of his ideas. At one point, he vetoed the entire state budget. Here’s how we characterized Sanford in 2005:

“Based on actions over the past three years, Sanford’s idea for a perfect South Carolina would find the state with very limited government, no income taxes, limited roles for public education and little government involvement with job creation. It’s almost as if all he would want government to do would be to pick up the trash and police the streets — and both of those things might be too expensive for him.”

Underinvestment in the Palmetto State during the Sanford years led to long-term problems with public education, college funding and more. And then there was the whole Appalachian Trail thing where the nation painfully watched the crumbling of his marriage.

Later redeemed, Sanford won his old congressional seat after the governorship. After Trump took over, Sanford criticized the president’s style and substance, which won him a primary opponent and led to the 2018 loss. And now with a lost boy look, Sanford seems to want to use six decades of living to make an impact.

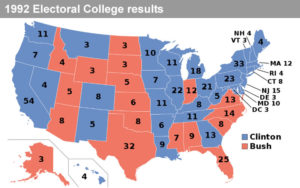

Rather than toying with a direct run against Trump, he’d be better suited to emulate the 1992 campaign of Ross Perot, who passed away earlier this month. The billionaire maverick snared almost 19 percent of the popular vote by talking in frank, easy-to-understand language about – guess what — government spending and debt. While Perot didn’t win any electoral votes, he changed the trajectory of the 1992 race and made it possible for Bill Clinton to beat incumbent George H.W. Bush at the polls.

Rather than toying with a direct run against Trump, he’d be better suited to emulate the 1992 campaign of Ross Perot, who passed away earlier this month. The billionaire maverick snared almost 19 percent of the popular vote by talking in frank, easy-to-understand language about – guess what — government spending and debt. While Perot didn’t win any electoral votes, he changed the trajectory of the 1992 race and made it possible for Bill Clinton to beat incumbent George H.W. Bush at the polls.

If Sanford runs for president as a Republican, he’ll lose in a heartbeat. He’ll be a blip on the screen because his Republican Party is gone. No longer the party of limited government and fiscal conservatism, it’s been drowned in a Norquistian bathtub by the blustering party of Trump where milquetoasts and yes-men thrive in a lapdog splendor, doing nothing for regular Americans.

As an independent presidential candidate, Mark Sanford can stretch his anti-debt message through November 2020 and make a much bigger impact than getting drowned in a tsunami of red-hat-wearing Trump lemmings who won’t hear what he’s saying. As an independent, he could be a spoiler like Perot and get the whole country focused on something important — the national debt that is slowly crippling us.

- Andy Brack’s new book, “We Can Do Better, South Carolina,” is now available in paperback via Amazon.

- Have a comment? Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com.

SPOTLIGHT: The S.C. Education Association

The public spiritedness of our underwriters allows us to bring Statehouse Report to you at no cost. This week’s spotlighted underwriter is The South Carolina Education Association(The SCEA), the professional association for educators in South Carolina. Educators from pre-K to 12th grade comprise The SCEA. The SCEA is the leading advocate for educational change in South Carolina. Educators in South Carolina look to The SCEA for assistance in every aspect of their professional life. From career planning as a student to retirement assessment as a career teacher, The SCEA offers assistance, guidance, and inspiration for educators.

The public spiritedness of our underwriters allows us to bring Statehouse Report to you at no cost. This week’s spotlighted underwriter is The South Carolina Education Association(The SCEA), the professional association for educators in South Carolina. Educators from pre-K to 12th grade comprise The SCEA. The SCEA is the leading advocate for educational change in South Carolina. Educators in South Carolina look to The SCEA for assistance in every aspect of their professional life. From career planning as a student to retirement assessment as a career teacher, The SCEA offers assistance, guidance, and inspiration for educators.

- Learn more: TheSCEA.org

USC’s board is the problem, not Caslen

To the editor:

![]() The problem with the USC president search is not with the candidate (in this case Lt. Gen. (Ret) Robert Caslen), but with the Board of Trustees. They have presided over perhaps one of the worst-run talent searches in recent memory.

The problem with the USC president search is not with the candidate (in this case Lt. Gen. (Ret) Robert Caslen), but with the Board of Trustees. They have presided over perhaps one of the worst-run talent searches in recent memory.

First, in terms of full disclosure, Bob Caslen is a classmate of mine from West Point. Despite attending West Point and serving in the U.S. Army together for cumulatively 24 years, we have never met – either during or after our “shared” experiences. Nonetheless, I have followed his career and achievements – especially over the last dozen or so years. He is, I believe, an excellent choice for USC president.

That said, Bob Caslen has been subjected to a baseless, almost slanderous, set of criticisms (most of them repeated, without any real understanding of the underlying facts, by members of the press) – none of them reflective of even a modicum of understanding of his experience and broad knowledge of university-level administration.

In counter-point to such criticisms, I will start with Forbes magazine which, in its 2018 college rankings, placed West Point at #27, while USC was ranked #211. Bob Caslen was superintendent (president) of West Point from 2013 to 2018.

But I digress. My main point and focus is on the shoddy, amateurish selection process orchestrated by the Board of Trustees. As much as I believe Bob’ critics and protestors (a stunningly small number of USC students, faculty and board members) are wrong-headed in their criticisms of Bob, they are right about a very important matter. The Board has failed to conduct a transparent, professional search and selection process. While I can only guess at the reasons for this, the evidence of their failures (which some may call incompetence) is overwhelming.

Sorry for Bob Caslen who, despite all these unjust criticisms and treatment – by both the protesters and board – has remained silent and professional. Sorry for the board and their inept handling of this whole process.

But most of all, I’m sorry for the students and faculty at USC who most likely will be denied the leadership and wisdom of a great academic leader, someone who has demonstrated the type of leadership and mentoring that has bridged differences across generations, as well as across political divides.

I will not blame Bob Caslen one bit if he withdraws his candidacy, or declines the opportunity (if offered). If he does either, I am sure it will not be his fear of being undermined from below by those few who oppose him, but because he cannot have faith that his boss, the Board of Trustees, can be counted on to do the right thing when confronted with hard decisions. At least that is what I believe.

— Robert E. Johnson, Summerville, S.C.

On McMaster’s involvement with USC board

To the editor:

The people of South Carolina, whose taxes support our public institutions of higher learning, deserve a say in choosing our public institutions’ leaders. It also seems to me that these institutions should reflect the morals and traditional values of our state.

Too often we hear of conservative speakers on college campuses today being harassed and unfairly targeted by liberal administrators and faculty. If my traditional values are not being passed down to other generations I do not want my tax money going to support these institutions.

We elected a conservative leader in Governor Henry McMaster. With a husband as a former member of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges. I cannot recall any instance in which a school was denied accreditation because of the method used in choosing its school’s president.

Not only should our governor have a major say as the voice of the people, the Board of Trustees and the faculty of each institution should mirror the conservative values of this state.

— Jane Haeflinger, Greenville, S.C.

Gerrymandering, Supreme Court style

To the editor:

On gerrymandering, Supreme Court style, I offer as Exhibit One the (old) Florida district of former U.S. Rep. Corinne Brown (now in prison). [Editor’s note: Click the link to see the map.]

The district line followed the St Johns River from Orlando to Jacksonville.

— T. C. Houghtaling, San Mateo, Fla.

Send us your thoughts … or rants

We love hearing from our readers and encourage you to share your opinions. But you’ve got to provide us with contact information so we can verify your letters. Letters to the editor are published weekly. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity. Comments are limited to 250 words or less. Please include your name and contact information.

- Send your letters or comments to: feedback@statehousereport.com

Speed limit: 25 mph

If you’ve been to this town, you’ll remember it. Where is it? Send your guess about the location of this photo to feedback@statehousereport.com. And don’t forget to include your name and the town in which you live.

Our previous Mystery Photo

Our July 12 mystery, “Patriotic tombstone,” is a photo sent to us by loyal reader Ross Lenhart of Pawleys Island. It shows the gravesite of Revolutionary War Gen. Francis Marion, the “Swamp Fox.”

Our July 12 mystery, “Patriotic tombstone,” is a photo sent to us by loyal reader Ross Lenhart of Pawleys Island. It shows the gravesite of Revolutionary War Gen. Francis Marion, the “Swamp Fox.”

Congratulations to: Dale Rhodes of Richmond, Va.; Debbie Causey of North Myrtle Beach; Philip Cromer of Beaufort; Daniel Prohaska and Bonnie Cooper, both of Moncks Corner; Jacie Godfrey and Barry Wingard, both of Florence; Will Bradley of Las Vegas, Nevada; George Graf of Palmyra, Va.; Harvey Shackelford of Newberry; Frank Bouknight of Summerville; Bill Segars of Hartsville; Steve Willis of Lancaster; James Gainey of Conway; and Jay Altman of Columbia.

Graf shared that the gravesite is Belle Isle Plantation Cemetery in Pineville. “Marion was born at his family’s South Carolina plantation in Berkeley County. A man of his time, he owned slaves and fought in the French and Indian War. While fighting against the Cherokee, he saw those Native Americans using landscape as a kind of weapon. After concealing themselves in the backwoods, they launched crushing ambushes. During America’s war of independence, Marion used those same tactics against the British Army. As a result, some historians call Marion the father of guerilla warfare.”

Segars said Lenhart stood on “patriotic sacred ground” when he snapped the photo of Marion’s grave at Belle Isle, which he said was “his brother Gabriel’s home, near Pineville in Berkeley County. Marion, whose demoralizing and evasive tactics of the superior British forces, later dubbed ‘guerilla warfare,’ earned him the name of Swamp Fox”

“He, along with the entire South Carolina Citizen Militia should be credited with winning the American Revolution as a result of the Southern campaign. Almost the entire Continental forces were beaten down until Marion and his men offered a glimmer of hope for victory to the downtrodden colonies.

“This site is not easy to find, but well worth the effort. Near St. Stephens on U.S. Highway 52, turn onto S.C. Highway 45. Continue through Pineville and turn right on Francis Marion Ave. The burial site is at the end of this road. For the GPS folks, go to N33ᴼ 27′ 14.33″ W80ᴼ 05′ 11.32″ and you’ll be there.” More people need to see this site.”

- Send us a mystery: If you have a photo that you believe will stump readers, send it along (but make sure to tell us what it is because it may stump us too!) Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com and mark it as a photo submission.

S.C. ENCYCLOPEDIA

HISTORY: University of South Carolina

S.C. Encyclopedia | The institution was originally chartered as South Carolina College on December 19, 1801. Its establishment was a response to the changing political landscape in the Palmetto State at the outset of the nineteenth century. South Carolina’s political leaders saw a new college as a way of bringing together the sons of the Federalist elite of the lowcountry with the sons of the upcountry Jeffersonians in order, in the words of the college charter, to “promote the good order and harmony” of the state.

It was intentionally sited in the relatively new capital city of Columbia to demonstrate independence from the influence of Charleston interests. Chartered by the General Assembly with an initial appropriation of $50,000, South Carolina College got under way remarkably quickly. In little more than three years of planning and preparation, the board of trustees hired a distinguished president and a faculty, established a curriculum, and constructed the first building on the new campus. Located a short distance southeast of the State House, the college opened on January 10, 1805, and in subsequent years enjoyed the generous annual support of the General Assembly, an unusual luxury for a state college in that era.

South Carolina College provided students a cosmopolitan education. Many early faculty members, as well as the college’s curriculum and rules governing student behavior, were drawn from the leading New England universities of the time.

By the end of the antebellum era, the institution stood as a bulwark of conservatism. The curriculum was a traditional classical one, focusing primarily on the study of literary works in Latin and ancient Greek and emphasizing the mastery of oratory. Boasting a distinguished faculty, a handsome campus, the latest scientific equipment, a large library, and generous public funding, South Carolina College ranked as one of the nation’s premier institutions of higher education, and it educated most of the state’s antebellum elite.

Then disaster struck. South Carolina’s secession unleashed the devastation of the Civil War, and South Carolina College paid dearly. In 1862 the institution was forced to close for want of students, and its buildings served as a military hospital during wartime. In 1866 state leaders revived the institution with ambitious plans for a diverse University of South Carolina. However, with a nearly empty state treasury, the university that emerged was barely a shadow of its former self. For the next century the institution struggled to regain the status it had once held.

After the war the political controversies of Reconstruction buffeted the university. In 1869 the Republican General Assembly elected the first African American trustees, and in 1873, when Republicans insisted that black students be admitted, influential faculty resigned and the state’s white elite largely abandoned the institution. The school’s first black students enrolled that year, as did the first black faculty member, Harvard graduate Richard T. Greener. Between 1873 and 1877 the institution was racially integrated and was the only southern state university to admit and grant degrees to black students during Reconstruction.

In 1877, members of South Carolina’s white leadership, led by Governor Wade Hampton, closed the institution to purge it of the Republican influences that they believed had sullied it. They reopened it in 1880 as an all-white Morrill Land Grant Institution: the South Carolina College of Agriculture and Mechanics. This institution thereafter became caught in the political upheaval of the last two decades of the nineteenth century. It went through several reorganizations in which the curriculum frequently changed and its status shifted from college to university and back again. During a brief period in the mid-1880s, it made significant strides toward regaining its antebellum glory, but again outside forces intervened to lower the college’s status.

The low point came in the late 1880s when Benjamin R. Tillman harshly attacked the institution. Tillman was the champion of those in South Carolina who thought the state should support an agricultural college, not a liberal arts university. Tillman convinced the state to establish Clemson Agricultural College in 1889 as an alternative to the University of South Carolina. In 1890 South Carolina’s voters elected him governor. Tillman stirred up class resentments and made attacking the university a central part of his program, calling it “the seedbed of the aristocracy” and promising to close it forever. Although he never followed through on his threats, the attacks crippled the institution. Enrollment fell to just sixty-eight students in 1893–1894, and in 1895 the institution’s entire book budget was only $71.

By the late 1890s the institution, again with the name South Carolina College, began a slow recovery from neglect. Women were admitted for the first time in 1895, and in the first decade of the twentieth century the curriculum was broadened. Enrollment began a slow rise, and the state rechartered the college as a university for the final time in 1906.

In the early part of the new century, the University of South Carolina struggled to compete for funding with five other state colleges (Clemson, Winthrop, the Citadel, the State Medical College, and the Colored Normal, Industrial, Agricultural and Mechanical College—later known as South Carolina State). A small, poor state, South Carolina simply could not afford to support six separate colleges and maintain a high standard of scholarship at any of them. When the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS) was founded in 1895, not a single college in South Carolina—public or private—qualified for membership. The University of South Carolina became the first state-supported institution in South Carolina to qualify for SACS membership in 1917.

The outbreak of World War II revived and transformed the university. As students left school in droves to enter the armed forces, the university initiated programs to help train civilians for defense-related industries. In 1943 the campus became home to officer training programs of the U.S. Navy and the trainees filled the dormitories, outnumbering civilian students. In the aftermath of the war veterans filled the campus, expanding the student body to new records and taxing the capacity of campus facilities.

However, the state continued to provide inadequate resources, and the University of South Carolina ranked at or near the bottom in comparisons with its peers in other states. In 1951 trustees named Donald Russell president, and he began a reform program that put the university on the road to recovery. He recruited prestigious faculty, established new academic programs, and revived old ones. With the support of the General Assembly, Carolina began a wide-scale construction program that modernized the campus. To meet the growing demand for higher education, in the late 1950s the institution began establishing regional campuses in communities such as Florence, Conway, and Beaufort.

With increasing levels of state funding and the arrival of the baby boom generation during the 1960s and early 1970s, Carolina grew from a student body of about 5,000 to nearly 25,000. Degree offerings expanded likewise, and under the leadership of President Thomas Jones, graduate education and research received growing emphasis.

Change was constant. The increasing size of the student body was matched with changes in the nature of those students. As the result of a federal court order, on September 11, 1963, Henrie D. Monteith, Robert Anderson, and James Solomon became the first of an ever-growing number of African American students to enroll at the university in the late twentieth century. Increasing numbers of international students came to Columbia as well.

In the late 1970s and 1980s, the university’s physical growth slowed but new degree programs and schools and colleges such as the College of Criminal Justice, the medical school, the College of Library Science, and the undergraduate Honors College helped expand educational opportunities. Renovations of older areas such as the Horseshoe ensured that the historic heart of the campus survived. Private fund-raising became a priority as state funding continued to lag behind growth, and the university emphasized international programs that attracted national attention. The quest for national recognition briefly stumbled when the university’s aggressive president James B. Holderman was driven from office in 1990 in the wake of a highly publicized spending scandal.

In the 1990s the University of South Carolina continued the drive for national recognition, emphasizing increased levels of faculty research and outside research funding. In 2001 the institution celebrated a legacy of two hundred years of educating South Carolinians by dedicating itself to continued improvements in the quality of service it offers to the Palmetto State. In 2001 the institution celebrated a legacy of two hundred years of educating South Carolinians by dedicating itself to continued improvements in the quality of service it offers to the Palmetto State.

— Excerpted from an entry by Henry H. Lesesne. This entry may not have been updated since 2006. To read more about this or 2,000 other entries about South Carolina, check out The South Carolina Encyclopedia, published in 2006 by USC Press. (Information used by permission.)

Available in paperbrack, err, paperback

Now you can get a copy of editor and publisher Andy Brack’s We Can Do Better, South Carolina! ($14.99) as a paperback.

The book of essays offers incisive commentaries by editor and publisher Andy Brack on the American South, the common good and interesting South Carolina leaders, such as former U.S. Sen. Fritz Hollings, civil rights advocate Septima Clark, former S.C. Gov. David Beasley and more. There also are discussions on civil rights struggles with which the Palmetto State continues to grapple. as well as commentaries on politics, governments, the hangovers of South Carolina’s past and her future opportunities.

We Can Do Better, South Carolina! is also available exclusively as a Kindle book for $7.99. Click here to purchase a Kindle copy.

- If you have a comment or questions about the book, please let us know at: feedback@statehousereport.com.

ABOUT STATEHOUSE REPORT

Statehouse Report, founded in 2001 as a weekly legislative forecast that informs readers about what is going to happen in South Carolina politics and policy, is provided to you at no charge every Friday.

- Editor and publisher: Andy Brack, 843.670.3996

- Statehouse correspondent: Lindsay Street

More

- Mailing address: Send inquiries by mail to: P.O. Box 22261, Charleston, SC 29407

- Subscriptions are free: Click to subscribe.

- We hope you’ll keep receiving the great news and information from Statehouse Report, but if you need to unsubscribe, go to the bottom of the weekly email issue and follow the instructions.

- © 2019, Statehouse Report. All rights reserved.

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!