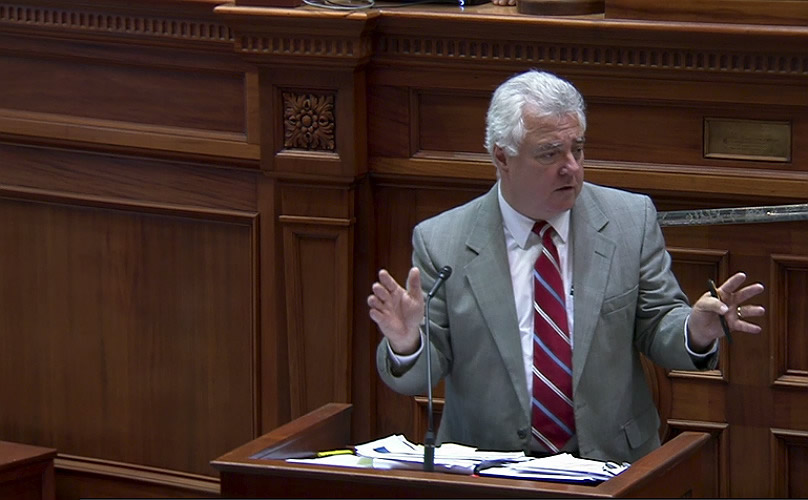

State Sen. Larry Grooms, R-Berkeley, discusses Santee Cooper on the Senate floor.By Andy Brack, editor and publisher | Anyone who doesn’t believe government doesn’t change needs to look to the South Carolina Senate. Compared to what it was 20 years ago, it’s almost a hot mess today.

Two of the differences are easy to see. First, some once familiar names that dominated headlines – Drummond, Fair, Courson, Ford, McConnell, Hayes, Leventis, Martin, McGill, Ravenel, Washington, Wilson, Thomas – are no longer there. Of the states 46 senators, only 11 serving today were in the chamber 20 years ago.

Two of the differences are easy to see. First, some once familiar names that dominated headlines – Drummond, Fair, Courson, Ford, McConnell, Hayes, Leventis, Martin, McGill, Ravenel, Washington, Wilson, Thomas – are no longer there. Of the states 46 senators, only 11 serving today were in the chamber 20 years ago.

Second, Democrats no longer rule the Senate roost. In the 1994 elections, Republicans gained control of the S.C. House for the first time in generations. Six years later despite having a Democratic governor, the state shifted more toward Republicanism as the state’s 46 senate seats split evenly between the two parties.

But just before the start of the 2001 session, longtime Democratic Sen. J. Verne Smith of Greenville shocked leaders by switching parties – and putting the state Senate in the Republican column.

That switch led to bigger changes that continue to impact the state Senate today.

When Republicans got control, they did two things quickly to upend the apple cart of Senate tradition which ultimately led to a more partisan, slightly less congenial body.

First, the GOP changed the seniority system of committee control. Prior to 2001, senior senators, no matter the party, ran Senate committees. But under GOP control, an extra component was added – political party. Under the new rule, powerful committee chairmanships were to be controlled by seniority, but by members of the majority party. In essence, the new minority Democrats, many of whom had years of seniority, no longer had control, often becoming ranking members to chairmen who were years younger.

What this change ultimately meant was political parties became much more important in the Senate. That meant more friction and less congeniality compared to two decades ago. It’s not as if these folks are overtly rude today, compared to years past, but there’s an edge of tension simmering just below the surface compared to the clubbiness of the past.

The second impactful rule change saw the new GOP majority increase the number of senators on the two major committees, Judiciary and Finance, from 18 to 23. That meant every senator was on one of the body’s two major committees. So a freshman, who in the past would have to wait a few years to move up the chain of seniority to get a seat on a major committee (and have more influence), automatically became part of a big committee.

This, too, increased partisanship as new, young Senate firebrands, often elected on platforms that were more left or more right of the general population, would speak out – and get media coverage – on big issues. No longer were freshmen relegated to the back benches.

Through the years, there have been other changes. This year, for example, the state’s lieutenant governor no longer is presiding officer of the Senate. For the first time, the person who controls the daily session is its new president. This shift has changed the day-to-day dynamic and, in some ways, has insulated the Senate from outside interference from external politics. (Remember, the state went through three lieutenant governors in a short spell after one got caught up in scandal, a successor left to lead a college and another took over briefly before a new election.)

Other changes limit debate and make it harder for one senator to gum up the legislative works. It can be argued this moves along needed legislation quicker, but the Senate is supposed to be the state’s deliberative body, not a rollercoaster for new laws.

Our state’s new Senate, because it is more partisan, also is less of a place where elected elites spend lives. In the hyper-partisan outside world, seemingly promising long Senate careers are shortened at the polls by frustrated voters, which leads to more Senate turnover, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It used to take a young senator a decade to get enough seniority to make a bigger difference. Now, someone elected a few years back is in the middle of the pack of seniority.

You might like new changes. You might not. But democracy constantly evolves, even in the S.C. Senate.

- Andy Brack’s new book, We Can Do Better, South Carolina, is available via Kindle.

- Have a comment? Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!