By Andy Brack, editor and publisher | To better understand why South Carolina is like it is, you need to read The 1619 Project.

This blockbuster re-telling of history not taught in schools likely will provide a new understanding about how America became a country — and how enslaved Africans played a vital role — not just a subservient one — in the creation of our democracy.

Recognizing this fundamental reality may help Americans cope with the lagging vestiges of slavery, still evident today in people’s attitudes and behavior, as well as our imbalanced economic system whose structure dampens the American Dream for far too many.

Recognizing this fundamental reality may help Americans cope with the lagging vestiges of slavery, still evident today in people’s attitudes and behavior, as well as our imbalanced economic system whose structure dampens the American Dream for far too many.

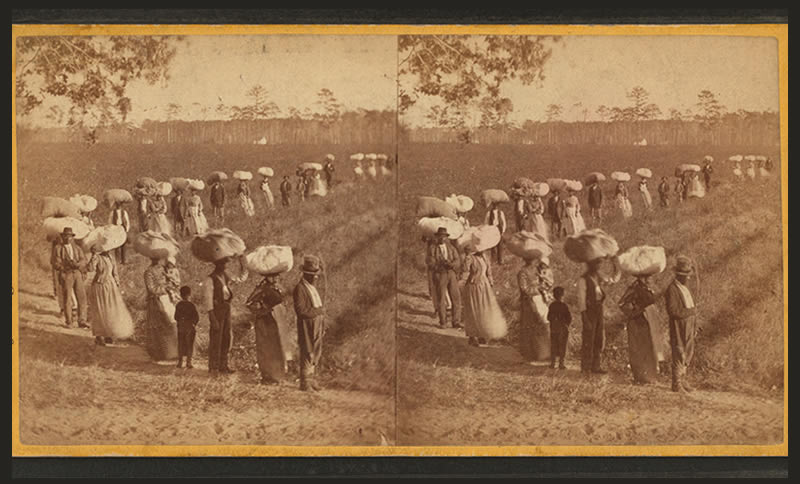

Four hundred years ago this month, the first enslaved Africans arrived in Virginia. The 1619 Project, related in a full issue of The New York Times Magazine, opened with these words: “No aspect of the country that would be formed here has been untouched by the 250 years of slavery that followed. On the 400th anniversary of this fateful moment, it is finally time to tell our story truthfully.”

What unfolds — including more than a dozen impacts of South Carolina’s on the system of slavery — is chilling in its violence and emotion. It gives fresh perspectives and uncomfortable truths on how this system of forced labor created enormous white wealth while dehumanizing people with dark skin:

“Out of slavery — and the anti-black racism it required — grew nearly everything that has truly made America exceptional: its economic might, its industrial power, its electoral system, diet and popular music, the inequities of its public health and education, its astonishing penchant for violence, its income inequality, the example it sets for the world as a land of freedom and equality, its slang, its legal system and the endemic racial fears and hatreds that continue to plague it to this day.”

“This piece unmasks the history of America not written in schoolbooks or taught in classes,” said Columbia public relations executive Bud Ferillo, who created the “Corridor of Shame” documentary about inequities in South Carolina schools. “It offers sobering, often painful, discoveries that should make us think and feel anew about our past, and where that leads us now.”

The Rev. Joseph Darby, an AME preacher in Charleston who is a longtime official with the NAACP, hopes the sweeping and frank account of America’s missing history will lead to systemic discussions and progress.

The Rev. Joseph Darby, an AME preacher in Charleston who is a longtime official with the NAACP, hopes the sweeping and frank account of America’s missing history will lead to systemic discussions and progress.

“The 1619 Project is an invaluable tool for everything from community dialogue to academic research to public policy,” he said. “The Project has done something rare by showing how slavery and its still lingering residue shaped and still hinders progress and equity in America.”

Darby shared that looking at the system of slavery and its successor caste system, rather than particular dates and events related, irritated right-wing critics.

“The National Review bemoaned the fact that the Project didn’t focus on more individual black history makers, and I understand why they raised that question. When discussions of race or any problem — like white urban terrorism – focuses on the “individual,” you can dodge frank discussion of the system that produced the individual.”

The Project, however, didn’t shy away from talking about the big impact of two individuals related to South Carolina. One was John C. Calhoun, a vice president and fiery senator who devised the brilliant political concept of nullification, which was the foundation of the cry of “state’s rights” that spread tentacles from the Civil War and the Jim Crow era to the Tea Party and white nationalism now rearing its head.

The Project also highlighted the story of decorated black Army veteran Isaac Woodward who was blinded in 1946 on the way home to visit his mother in Whitmire. The Project shares that his maiming was “one of the catalysts” for what became the modern civil rights movement, which U.S. District Judge Richard Gergel of Charleston addressed this year in a book titled Unexampled Courage.

“I was delighted The 1619 project gave such prominent treatment to the Woodard story,” Gergel told us. “I also was glad to see my central thesis accepted.”

Anyone in state or local government — particularly elected officials — must read The 1619 Project to understand how America became America. It isn’t comfortable, but it’s a step toward dealing with a system that’s still unequal for too many.

Andy Brack’s latest book, “We Can Do Better, South Carolina,” is now available in paperback and for Kindle via Amazon.

- Have a comment? Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com.

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!

Thank you Andy for what you do at the state level, the county level, organizations and community levels, all the way down to SC citizen actions and behavior level. Please don’t stop.

I read every word of The New York Times compelling magazine issue containing The 1619 Project and wish everyone could have access to it. It was brilliant and deserves widespread dissemination. I am so glad you brought this up for your readers. It is such a painful story.

Another powerful testimony to the lasting impact of slavery is contained in Randy Neale’s brilliant play, Last Rites, on now at Pure Theatre. Set in the midst of the Detroit riots of 1967, it uses three characters to show the gulf that divided and divides people and the rage that oppressed people feel, then and now. Randy Neale lived near Detroit at that time and has been haunted by the events then; his play, which runs for only a few more days, ought to be revived and shown elsewhere.