By Lindsay Street, Statehouse correspondent | The shuttering of restaurants and schools has lashed South Carolina farmers. The exact toll will be unknown for months but some fear the downturn in markets from the coronavirus pandemic will cause farms already on the edge to suffer or close.

“The last five years have been insane,” said Clemson University agribusiness professor Adam J. Kantrovich said. “Hurricanes, freezes, the trade war and now this.”

He said the state’s response to the coronavirus pandemic and potentially the virus itself added more hurt that may not be relieved by aid packages.

- As the trade war waged in 2019, delinquencies on South Carolina farms increased as some weighed hard realities. See our August 2019 coverage here.

Some federal aid is already expected for farmers, but state disaster aid was held up after a one-day legislative session this week ended without an agreement on funding state government or releasing $180 million in pandemic aid.

But amid the challenges, there could also be opportunity to strengthen and bolster locally grown foods, according to Kantrovich and South Carolina Farm Bureau media liaison Stephanie Sox.

On the farm

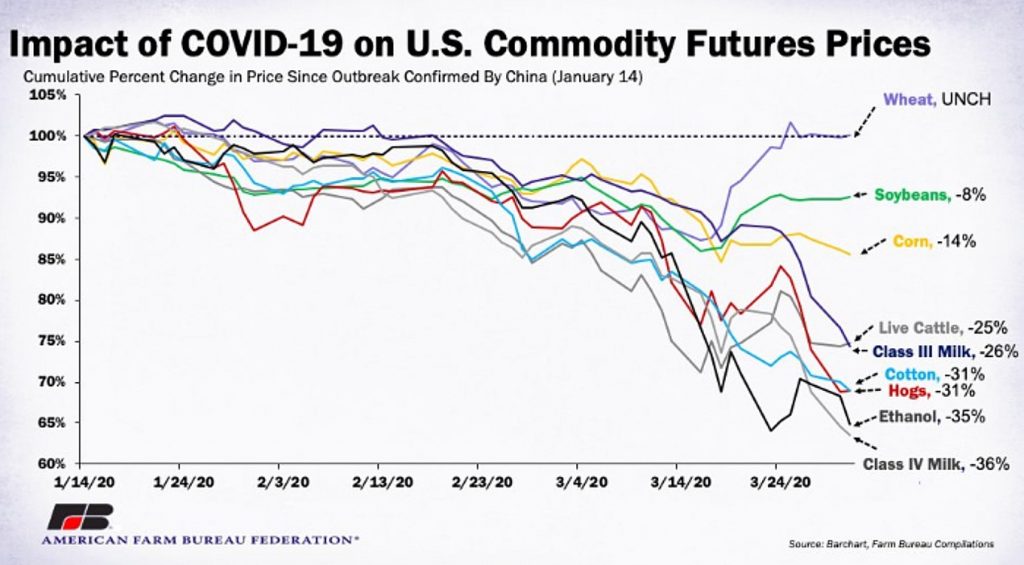

An updated analysis by the American Farm Bureau Federation shows crop and livestock prices falling to levels that “threaten the livelihoods of many U.S. farmers and ranchers.”

The federation said the closing of schools and restaurants has led to a “downward spiral” in crop and livestock prices. It reported this week that corn prices since January are down 15 percent, soybean prices are down 10 percent, and cotton is down nearly 30 percent. Beef, pork and milk prices are all down around 30 percent.

The federation said the closing of schools and restaurants has led to a “downward spiral” in crop and livestock prices. It reported this week that corn prices since January are down 15 percent, soybean prices are down 10 percent, and cotton is down nearly 30 percent. Beef, pork and milk prices are all down around 30 percent.

Kantrovich said hard numbers on farm closures will not be available for months, but he already knows of dairy farms lost this year in South Carolina. Sox addedmany wholesalers and direct-to-consumer farms in the state have been “creative and resourceful on finding new markets.”

For example, Senn Brothers Produce’s Jake Senn said the West Columbia distributor was split evenly between retail and restaurant, but all that has changed in the last month.

“People will always eat, people have to eat. Where the restaurant business fell, our retail business grew,” Senn said, adding that despite retail increasing, many staff members had to be reduced to part-time and a handful were laid off.

- Buy it fresh: The S.C. Department of Agriculture has launched a list of farms, wholesalers and markets offering direct-to-consumer sales. See the list here.

Labor and health

Two major issues that will determine the ultimate impact of the pandemic on farmers are access to labor and access to health care, according to Kantrovich.

In the last decade, many farms in the state have used temporary workers from foreign nations, known as H-2A workers. Federal authorization allowed South Carolina about 6,000 of these nonimmigrant workers in 2019, Kantrovich said. He said these workers are vital to keeping farms running in the state since local labor appears unwilling to do the work at the pay offered.

But foreign labor is vulnerable for two reasons, he said. First, the housing is typically dormitory style where disease can spread easily if picked up on a trip to town and, second, foreign countries that supply the laborers could close borders in the pandemic — leading to a worker shortage in the state.

That leaves farmers wondering whether they can plant or harvest, and if they do, risking a sickened workforce. Or sickening themselves or family.

“It is a significant concern,” Kantrovich said, adding it has been a concern nationwide among farmers. “(But) these farmers are willing to put themselves up to do what they need to do.”

South Carolina’s farmers are also similar to peers elsewhere in the nation: they live in rural areas with limited access to health care and, on average, are pushing 60-years-old. In other words, they are among the people most at risk from dying from COVID-19.

“They are much more susceptible to being harmed by the virus itself and in essence are risking death (by continuing to farm),” Kantrovich said.

And with the added stress of lost income, there is another pandemic surging for farmers: mental health. Kantrovich and Sox said initiatives are forming in the state to help.

‘There is opportunity’

Amid all the concerns, however, there is a conversation about reforming the industry. Sox said discussions about making agriculture more resilient has been ongoing for decades.

“Agriculture as a whole is probably one of the most progressive industries in the world and farmers have found a way over and over and over to respond to environmental needs, respond to consumer demands and doing it all with less land, less resources through technologies,” Sox said. “They have always met that change head on.”

But there are some obstacles.

Kantrovich said a “middle ground” needs to be found between cheap imported food and locally-grown food, adding that some of it will come down to consumer expectations on availability and cost.

Senn said local produce can cost up to 40 percent more than imported produce. And most of that additional cost is due to labor, according to Kantrovich. He said the industry needs federal-level legislation and policy changes, and possibly subsidies at the state level to help it compete.

Already, consumers appear to be shifting choices when it comes to food, such as buying directly from farmers, raising their own chickens or starting a garden. Kantrovich said the more people get interested in growing their own food, the more they are likely to support locally-grown food.

“I hope folks will remember that buying local and supporting local is important even if we’re not in the middle of a pandemic,” Cox added.

- Have a comment? Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!