By Skyler Baldwin, special to Statehouse Report | South Carolina has a growing trash problem, in part, because volunteers stayed inside during the pandemic. They worked fewer hours cleaning highways, byways and waterways, according to anti-litter leaders.

And on top of that is the state’s booming development, which causes even more problems, according to neighborhood groups, local government and statewide organizations.

“Every time there’s a new roadway or new houses put in place, there are new travelers using those roadways, and the litter certainly follows suit,” said Jason Kronsburg, director of the City of Charleston’s Department of Parks. “Contractor debris, pickup-truck related, delivery stuff — with the booming economy here, litter is going to happen.”

The accumulation of litter, leaders say, is also triggering issues more urgent than unsightly roadways.

“It’s not just an eyesore,” said Sarah Lyles, executive director of the statewide PalmettoPride anti-litter organization. “We want people to understand that with Charleston, and tourism being the primary industry, a heavily littered place is going to be dangerous for drivers and pedestrians. It detracts from natural beauty, and it takes resources to clean that could be applied elsewhere. And of course, it pollutes our waters and harms the environment.”

“It’s not just an eyesore,” said Sarah Lyles, executive director of the statewide PalmettoPride anti-litter organization. “We want people to understand that with Charleston, and tourism being the primary industry, a heavily littered place is going to be dangerous for drivers and pedestrians. It detracts from natural beauty, and it takes resources to clean that could be applied elsewhere. And of course, it pollutes our waters and harms the environment.”

Litter discarded along roadways or elsewhere could be contributing to the worsening coastal flooding. Carried by rainwater runoff to storm drains, garbage can clog local drainage systems.

“I don’t think people realize that when you have litter that gets into storm drains, it prevents them from working to allow water to flow through, and that impacts flooding, particularly with creeks and tributaries,” Lyles explained. “We have to keep those waters flowing freely.”

Litter also creates bigger costs

The mess on the side of the road and in streams goes beyond plastic bags, straws or cups tossed aside.

“We can think about litter as waste products that have been discarded incorrectly or at an unsuitable location or in excess,” said Betsy La Force, the S.C. Coastal Conservation League’s communities and transportation senior project manager. “Landfills represent a lot of that. Even if your trash is ending up in a trash can and ultimately landfill, the footprint, the impact of your waste, is still contributing to climate change and greenhouse gasses.

“There’s a much larger environmental cost to sending organic waste to the landfill, where it’s unable to break down in a natural way,” she said. “A lot of people think of food waste as being organic, breaking down on its own, but when it ends up in a landfill, covered up by plastic and compressed down to save space, it’s trying to decompose without oxygen, and that’s what produces the methane gas.”

According to La Force, municipal solid-waste landfills are the third-largest source of human-related methane emissions in the U.S. and the leading contributor to climate change according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

South Carolina generates roughly 4.2 million tons of municipal solid waste per year, according to La Force. More than 70 percent of that ends up in landfills, “consuming valuable acreage, blighting the landscape, contaminating the soil and waterways and emitting noxious, polluting gases like methane into the air.”

Efforts abound, but more needed

With the issue growing worse every year, local groups of all sizes have implemented programs and efforts to help reverse the impact of litter.

In addition to the City of Charleston’s Keep Charleston Beautiful program, the city council in May adopted its climate action plan, which includes 12 initiatives and 51 plans to address climate change; one chapter focuses entirely on waste.

That chapter details 10 plans of action to reduce the impact of waste on the climate in the Lowcountry, including the continuation of supporting the elimination of single-use plastics, performing a garbage audit and increasing the number of recycling stations in public spaces.

The South Carolina Aquarium’s “Litter-Free Digital Journal,” launched in 2016, has kept a record of data from members of the community by logging individual pieces of trash.

In 2017, 9,746 83,859 pieces of trash were logged, and 2,333 179,271 were recorded in 2018. The number jumped to 32,600 334,835 in 2019 and more than doubled jumped in 2020 with 74,977 508,232 pieces of trash counted. So far, in 2021, 28,495 232,168 pieces of debris have been collected.

EDITOR’S NOTE: An earlier version of this story underreported the data on debris collected., according to the S.C. Aquarium. The errors have been changed above. We apologize for the errors.

Hotline offers way to bust litterers

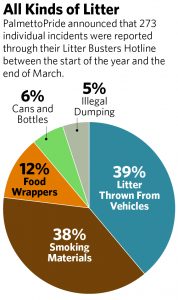

Across the state, PalmettoPride operates a Litter Busters Hotline, an awareness campaign that allows members of the community to be a part of enforcement. People can call in to the hotline when they see someone littering, or a hotspot that needs to be cleaned up.

“We are one of the few states that have one of these hotlines,” Lyles said. “It’s just a way to empower citizens and let them be a part of the enforcement of litter laws and help educate people of the econsequences of their actions.”

PalmettoPride boasts four program areas in total, including education, where they visit classrooms to teach students about littering and community cleanup. But, both Lyles and La Force said more needs to be done at every level to make a dramatic difference in the problematic effects of litter.

“If we can figure out how to encourage more residents to compost, even on their own, or from a municipal collections standpoint where they can roll out food waste and kitchen scraps across the city — it needs to be easy, affordable and accessible, and right now, it’s not,” La Force said.

Composting, she said, needs to be a big priority for solutions.

“That will really help contribute to other issues that are interrelated,” La Force said. “It can make soil more absorbent for stormwater, and it can help establish that farm-to-table loop that many restaurants that source local produce from local farms. It just expands out so far.”

Since implementing the hotline, Lyles said she has seen fewer calls and reports of littering in the area. But, she said that could have been due to the pandemic keeping people inside more often. At the moment, she said, it’s difficult to determine where the numbers are trending.

Report litter through PalmettoPride’s Litter Buster hotline by calling 1-800-7LITTER, online or through their Litter Buster app. A version of this story first appeared in the Charleston City Paper where Baldwin is a staff writer.

- Have a comment? Send to feedback@statehousereport.com

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!

Pingback: Is our town turning into a landfill? – Jarrod Andrews