EDITOR’S NOTE: This is one of the most interesting history stories we’ve read of late. You’ll learn how a South Carolina man became the first Black serviceman to be awarded the congressional Medal of Honor – in 1864.

By Herb Frazier | Civil War battles freed Robert Blake from slavery at a Charleston County rice plantation on the South Santee River. Then a rebel attack thrust him into a near-death moment of bravery near Johns Island that led to a historic Congressional Medal of Honor being pinned on his chest.

Blake was among 400 enslaved people the Union Navy rescued in late June 1862 during a raid on the Blake Plantation near McClellanville. Blake and about 20 enslaved men from the plantation later entered the Union Navy. Blake’s action during a Confederate attack at 6 a.m. on Christmas Day 1863 on the Union gunboat Marblehead earned him the nation’s highest military decoration.

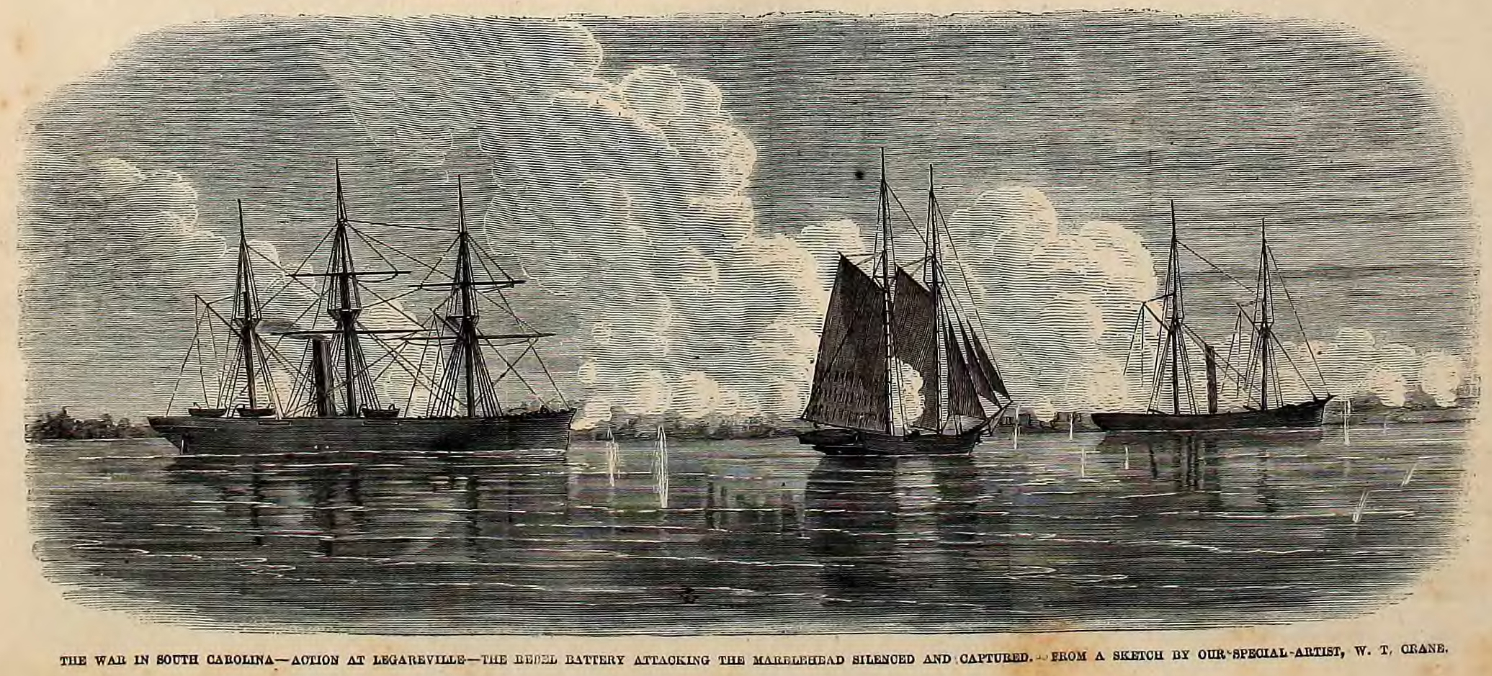

As the vessel patrolled the Stono River near Legareville, a summer retreat for area planters on Johns Island, an exploding Confederate shell killed the powder boy and knocked Blake to the deck. A bruised Blake jumped up, stripped to the waist and began running powder boxes to the gun loaders.

The Marblehead’s captain asked Blake, the boat’s cook who had no combat role, what was he doing. Blake answered with gospel song lyrics inspired by Revelation 6:15-17: “Went down to the rocks to hide my face, but the rocks said there is no hiding place here. So here I am, sir.” Blake was later promoted to seaman.

Blake received the medal in 1864. He is considered to be the first Black Civil War combatant to “actually” receive the medal of honor in person. Civil War soldier and medal recipient William Harvey Carney, best known for holding the American flag high during the Union’s July 1863 assault on Battery Wagner at Morris Island near Charleston, received the medal in 1900, 36 years after Blake. But Carney is credited as the first Black medal recipient because his heroism occurred before Blake’s.

As of March 2023, 3,525 service men and women have received the medal, according to the Congressional Medal of Honor Society. Blake, who is among 94 Black medal recipients, is listed in the Medal of Honor Museum on the USS Yorktown at the Patriots Point Naval and Maritime Museum in Mount Pleasant. But unlike Carney’s heroism, Blake’s story is not prominently displayed.

Area man may be related to hero

Darius Brown, a research assistant in the Center for Family History at the International African American Museum, said he believes he is related to Blake.

“[It is] awesome to know that another potential relative of mine was a war hero,” said Brown, who grew up in Beaufort and has family ties to the South Santee. “Like my other numerous Civil War relatives, their stories should be heard and honored.”

Joseph McGill Jr., a Black Civil War reenactor and history and cultural coordinator consultant at Magnolia Plantation and Garden, laments that Blake may remain a lesser-known Civil War hero since the popularity of Civil War reenacting has declined. Reenactments gave Black Civil War buffs the stage to interpret the lives of Black sailors and soldiers like Blake and Carney. But reenactments are no longer popular, he said.

Dylann Roof, a Confederate-flag-waving avowed racist, tarnished the shine of Civil War reenactment in June 2015 when he killed nine members of Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, McGill said.

A Winyah Bay exodus

Arthur Middleton Blake purchased a colonial-era rice plantation in 1843 that by the time of the war covered more than 9,000 acres. During the fighting, Confederates used the plantation as a base for blockade-running boats. When Union gunboats approached, the Confederates opened fire. The Union returned fire, and seamen and marines went ashore. After a brief skirmish, some 400 enslaved people, including Blake, boarded the Union boats. Today, the Blake Plantation is the Santee Coastal Reserve Wildlife Management Area.

The Union called the formerly enslaved people “contraband” after they became under Union control. “Contraband of war is property taken during a war,” said East Cooper historian Suzannah Smith Miles. “Unfortunately, in this instance, it meant human beings that were the property of their owners.”

The formerly enslaved people were taken to North Island in Winyah Bay near Georgetown where Robert Blake and about 20 other men entered the Union Navy, said Miles, a historian at The Village Museum in McClellanville. Records show that Blake entered the U.S. Navy on June 30, 1862, she said. Other men also entered the military at that time. Some of them returned to the Blake Plantation after the war, she added.

Enslaved people on North Island experienced destitute conditions with limited clothing and food. An informant in July 1862 told the Union that 500 rebels near Georgetown were preparing to attack North Island “with the intentions of destroying the contrabands … which number 700 men, women and children,” according to Barbara Brooks Tomblin, author of Bluejackets and Contrabands: African Americans and the Union Navy.

By 1863 and 1864, people on North Island, including people from the South Santee, were moved to Port Royal in Beaufort County and other coastal camps under Union control. The Union seized Port Royal in November 1861 during a heavy naval bombardment enslaved people called “the big gun shoot.”

Growing up in Beaufort

In 2017, Brown said he began researching his family and compiling oral histories “to go back as far as I could,” he said. “I always knew that I had ancestors who were enslaved by the Blake family,” said Brown, 25. “My great-grandmother, Margaret Jiles Brown, talked about it when I was younger. She said her family came from the Santee near Georgetown.

“I haven’t made a [family] connection with Robert Blake,” Brown admitted. “He is hard to find in the records. It is possible that I am related [to him as] a distant cousin because I have two sides of my family that came from that plantation,” he said. Brown said some of the South Santee families who were brought to Beaufort settled in the Gray’s Hill community where he grew up.

Brown has discovered kinship ties with more than 20 formerly enslaved men from the South Santee who were taken to Beaufort. A few of them joined the U.S. Army and participated in a June 1863 raid on the Combahee River that freed about 700 enslaved people, he said.

Discovering ancestors who fought to end slavery “gives me a sense of pride,” Brown said. “I have close to 30 relatives who fought in the Civil War, and that tells me they weren’t just concerned about their freedom but the freedom of others.”

Herb Frazier is special projects editor with the Charleston City Paper, where this story first appeared. Have a comment? Send to: feedback@charlestoncitypaper.com

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!